Features Overview

Photo courtesy of Sanae Yamada

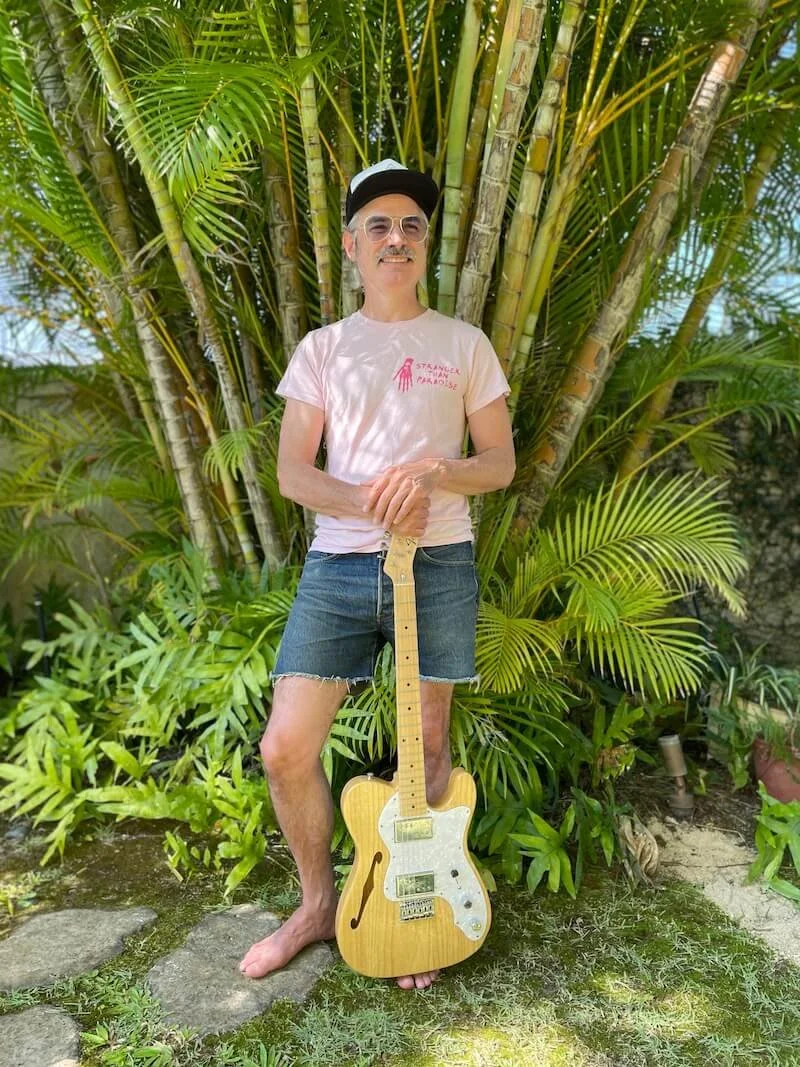

Catching Up With Rose City Band

Though the grooves of Rose City Band’s Garden Party go down easy, when he was coming of age in Wallingford, Connecticut in the 1980s, Ripley Johnson defined himself by what he hated. “Being an adolescent you’re just against everything, so we were against all of the synth pop and ’80s haircuts,” says Johnson. “Everything was neon and there were yuppies and Reagan.” As a teenager, Johnson longed for more adventurous sounds, drawn to punk bands like Black Flag and JFA through his love of skateboarding and Thrasher Magazine.

“When you grow up in a small town you’re finding clues everywhere about the counterculture,” said Johnson. “It was really an act of sleuthing.” Punk rock shifted to a fascination with the 1960s as Johnson began experimenting with psychedelics and the music that came along with them. Indulging in Jimi Hendrix and Neil Young was a form of resistance. “Sticking it to the man,” says Johnson.

Inspired by a friend, Johnson left Wallingford to chase his dreams of living on the West Coast. “I got on a Greyhound bus,” Johnson explains. “They were running this special for a while. I’m pretty sure it was $69 to go anywhere in the country.” So, Johnson saved up his money, spent three days on the bus and found himself in California where he enrolled at UC Santa Cruz and formed his first band, Botulism.

Heavily influenced by Blue Cheer, the Stooges and the Japanese label Psychedelic Speed Freaks, Botulism cranked their amplifiers to the maximum volume, and cleared rooms with their deafening noise. “Looking back, I’m kind of proud of my younger self,” said Johnson. “I think we were pretty terrible in a lot of ways, but we were committed. We didn’t care that everyone left.”

Once Johnson graduated, Botulism moved to San Francisco, where they released one 7” record and found little success. After Botulism, Johnson’s music taste shifted to free jazz, minimalist music and Krautrock. The repetitive quality of these genres led Johnson to a musical epiphany. “There’s some music that people just respond to intuitively because it’s a primal thing,” Johnson says. “And so, I thought if I find non-musicians, I can teach everyone a chord and experiment with that.”

The group of non-musicians jammed for a couple years but never played a show. Uninterested in making an album or playing live they went their separate ways. Still passionate about the primitive project, Johnson recorded and released a solo 10” record titled Wooden Shjips which became the name of his first major band.

Johnson lost his job in San Francisco’s tech industry during the 2008 financial crisis. The solution, and artistic challenge to his unemployment was to form a new band that “said yes to everything,” said Johnson. So, he put Wooden Shjips on the backburner and started Moon Duo with his wife, Sanae Yamada.

Their records well received, Moon Duo hit the road. “It was just the two of us, and we could travel pretty cheaply,” said Johnson. “We went to Finland and Estonia. We went to Moscow, Ukraine and Sardinia. Just all over.” After touring consistently for a few years, Johnson and Yamada settled in Portland, Oregon in 2012. Johnson was drawn to Portland’s gentle qualities compared to San Francisco.

“There’s a bigger sense of the natural world even if you’re living in a neighborhood,” said Johnson. “It’s much greener.”

“For a while I just kind of hid behind fuzz,” said Johnson of the music he had created over the years. “I was really into fuzz and distortion. More obscure vocals and loud music.” Over the years, as his projects mellowed, Johnson longed for a new sound. “I felt that there was a part of my musical personality that I hadn’t expressed yet,” said Johnson. “I wanted to do something with a little twang in it.”

“When I was younger I had more energy, everything was fast and groovy,” said Johnson of songwriting. “The Rose City Band stuff comes from just strumming the acoustic guitar.” Rose City Band is the fruit of Johnson’s appreciation of music and eclectic taste. “I’m a huge Neil Young fan from childhood. But also the Grateful Dead, The Stones, their more pastoral vibe, and The Band, Bob Dylan,” said Johnson. “And then I’m really into country like Waylon

Jennings, Willie Nelson and Lucinda Williams, it’s just a side of me that I really respond to in music and something that I’ve always wanted to do.”

For years Johnson longed to form a country rock band. Due to the pandemic, he released three albums as Rose City Band before ever playing a live show. As restrictions loosened, Johnson recruited a handful of local musicians to perform live as Rose City Band. “We got really tight and we played this Mississippi Studios show. Afterwards Sanae was like, ‘You did it, you got your country rock band.’” The sound in Johnson’s head had come to life, inspired by Portland summers. “The feeling of going for a bike ride or sitting on your porch,” said Johnson. Johnson’s attitude towards life is reflected in his music.

“He’s got a very zen vibe to him,” said Dustin Dybvig, drummer of Rose City Band. “I look up to his calmness, especially on the road.”

“Initially I didn’t love touring,” Johnson says. “I’m not super into being the center of attention. I still get anxious about playing on stage and I don’t really want to be in the spotlight.” There is uncertainty with live performances. “It’s sort of akin to throwing a party,” said Johnson. “You’re not sure if people are going to come to your party or not.” Performing with other people helps Johnson overcome his anxieties. “It’s like a safety net,” says Johnson. “Everyone’s carrying the load.”

Johnson especially feels a sense of security when performing as Rose City Band. “The guys in the band are all really enthusiastic about music, they all want to play,” said Johnson. “They come alive on stage and get this energy that is just so contagious.”

Rose City Band is composed of five musicians, the largest group that Johnson has performed with. “It takes the pressure off because everyone is contributing,” Johnson says. “If you’re well-rehearsed and everything is going well and you have good material, you have this confidence that you’re going to go out and crush it.”

“You’re a crew,” Johnson says of being in a band. “You develop that the more you play, especially when you’re on tour. You can rehearse every week for a year and you’ll never get as tight as doing a one or two week tour. You get so good so quickly because everyone is responding to each other, making micro adjustments all the time and bonding in a way that I think is really special.”

“The live show is so ephemeral, it’s a different type of beauty,” Johnson says. “I don’t like recreating the record live. I find it’s often better, especially live, if someone brings something you hadn’t thought of like a different bass line or keyboard sound. It keeps it fresh to me.”

While Johnson has grown to appreciate touring, his favorite part of being a musician is making albums. “Records have been so important to me in my life,” Johnson says. “It’s almost like a drug. I rely on records to cheer me up or calm me down.”

“Making the record is one thing, and playing live is a completely different thing,” Johnson says. “The record stands as what it is. That’s me trying to get the sound that’s in my head exactly how I want it on the record and indulging myself.”

The live band is a whole different experience. “I don’t feel like I really know what I’m doing most of the time and I embrace that,” Johnson says. “A lot of the music that I like is outsider kind of music. Private press, weird music that was never successful for whatever reason. Or was just done in a different way and appreciated later.” Johnson tries to retain the amateur, outsider sound in his music. “I do just by virtue of not being a great musician,” Johnson says. “I can’t do everything, but I can do these things. I record most of the stuff at home, so it hopefully retains a humble, homemade sort of feel.”

Garden Party is a summer album and Johnson looks forward to performing the songs live. “I feel like I really lucked out,” Johnson says of the touring band. “Everyone’s fired up in this band, just having a good time.”

Daily Emerald/Kemper Flood

‘Just become the weather,’ a look at the life and art of Leonardo Drew

Bantering back and forth like two old friends, Leonardo Drew and Jordan Schnitzer recollect old memories and riff off of each other as they saunter through the heavy metal doors of the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art on campus. Led by museum staff, the pair are escorted up a daunting flight of marble stairs. At the top, Drew’s mouth spreads into a wide smile as he is confronted with his work, “215B.”

“215B” is the first visible work of art in the exhibition Strange Weather, which opened at the JSMA on Oct. 21. Sprawling across three museum walls, the work appears to extend an arm and invite the viewer in for a better taste.

“I believe these works should act as mirrors,” Drew said of his art. “There’s no way you won’t find some through-line that we all are part of.”

Drew is a Brooklyn-based artist best known for his large-scale, abstract work. Born in Tallahassee, Flo. but raised in the projects of Bridgeport, Conn., Drew knew he was an artist at a young age.

“Even though I’m named Leonardo and my mother says she knew for whom she named me, she did not,” Drew said to a captivated audience in a lecture held at PLC on campus. “Only sometime later, after many beatings for being named Leonardo in the projects, the nuns told me, ‘Oh, like Leonardo Da Vinci?’ and I was like ‘There’s another Leonardo?’”

Despite his mother unknowingly bestowing him an artist’s name, she did not encourage his early artistic endeavors. “My mother is a strong spirit, definitely an influence, but she did not understand,” Drew said. “You got to understand that if you’re growing up in the projects and someone in school gives you a test paper and you start drawing all over it, it’s time to stop you from doing that.”

But Drew didn’t stop. He was scouted by DC and Marvel Comics as a teenager, the result of having his drawings published at age 13.

“When Marvel and DC approached me, it seemed like the correct thing to do, to use your talent to get out of the projects,” Drew said. “Once I saw Jackson Pollock though, that was canceled.”

Pollock’s work inspired Drew to transition from drafting and two-dimensional art into a world of visceral three-dimensional art. Drew attended Parsons School of Design in New York for two years before transferring to The Cooper Union School of Art in New York City. At Cooper Union, Drew met Jack Whitten, a professor who he describes as both a father and mentor figure.

“What he brought to the table was this undying curiosity to continue,” Drew said. “That even though you were not accepted in the mainstream, there was still a connection to a larger world. It seemed to not be inclusive but actually, there are no barriers when it comes to art."

The year was 1985 and Black artists like Drew and Whitten were given few avenues of representation. At the time, the expectation was that they would teach or travel, but rarely find success in the mainstream.

“If you’re a Black artist, there’s a door that you have to go through,” Drew said. “I never really believed that. It was a different kind of work that I was determined to change and challenge.”

“Great art grabs you and shakes you and makes you think,” Schnitzer said, gazing up at “215B” in his gallery. “So he’s already won half the battle.” Schnitzer went on to cite Drew’s “genetic predisposition towards aesthetic” as the other half of his triumph in surviving the world of professional artists.

Drew has made a name for himself in the art world and proven that his bold and abstract art has a place in the mainstream. His works have been shown across the globe, and in notable museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Solomon R. Guggenheim in New York and the Tate in London.

Recently, Drew has spent time traveling in Peru and China, which has influenced him to utilize new techniques, such as the inclusion of color, in his works. “This planet is full of so much,” Drew said. Travel informs his artistic vision, and he acts “as an antenna receiving new information” in the places he visits.

Drew is constantly working and reworking his art, taking things that are “finished” and creating the next piece. “When you get comfortable, tie your hands and try again,” Drew said of his experience making art. “There is no such thing as a mistake.”

As far as legacy, Drew is not concerned with his impact on the world, so much as his desire to make art and his purpose as an artist. “These works can go on to disintegrate,” Drew said. “But for me they were important.”

At age 62, Drew is approaching a phase of life in which most people contemplate retirement, though he has no plans of seizing to make art. “I am absolutely an addict,” Drew said. “Making, making, making to the point where my hands and everything are starting to give problems.”

Despite his extensive career and the physical implications of being an aging artist, Drew prevails. “I need to continue to challenge myself,” he said. “That’s what keeps life interesting for me.”

Drew’s work “215B” is available for viewing at the JSMA until April 7.

Daily Emerald/Stella Fetherston

In conversation with Oregon Book Award finalists

Literary Arts’ Oregon Book Awards took place Monday, April 8 at the Armory in NW Portland, hosted by Kwame Alexander. The awards sprawled across seven categories featuring fiction writing, poetry, nonfiction, young adult and graphic literature.

Five finalists were nominated for the reputable Ken Kesey Award for Fiction. Of the finalists, Patrick deWitt, a Canadian American novelist, prevailed, winning the award with his latest novel, “The Librarianist.”

The novel follows Bob Comet, a retired Portland librarian who finds himself dreaming of a seaside hotel from his childhood. In a review of the novel, The Washington Post described it as, “gentler and less strange than his previous books.” It currently sits at a 3.4 star rating on Goodreads.

While the Oregon Book Awards proudly highlights local authors, the national and global reach of the authors’ backstories can be traced throughout their literary articulations. From Canada to Armenia to San Francisco, these authors reconstruct the world as we know it through their fictional retellings.

Lydia Kiesling, "Mobility"

Lydia Kiesling, author of “Mobility,” was one of the finalists for the Ken Kesey Award for Fiction. A novelist and culture writer, her work has received national attention and has been published by notable outlets including The New York Times, The New Yorker online and The Cut.

Her novel, “Mobility,” follows the life of Bunny Glen, an American teenager whose Foreign Service family is stationed in Azerbaijan. The novel begins in 1998, enmeshing girlhood with the rush for Caspian oil and the rise of the War on Terror. The reader ages with Glen as she navigates a career in oil and consequently, class, power and political dynamics.

Though her career as a writer is worlds away from the oil industry, “Mobility” was loosely inspired by Kiesling’s nomadic upbringing.

“My dad worked for the State Department and that means we moved around a lot,” Kiesling said. “One of these countries was Armenia, a land cursed without oil reserves, where people migrate out, not in.”

While contemplating a setting for her book, Keisling studied Azerbaijan, an oil-rich neighbor of Armenia.

“As I was doing that I realized that I wanted and needed to put it in a broader geopolitical context,” Kiesling said. “I got really interested in oil as one of the ways to give that context.”

The similarities between Kiesling and main character, Bunny Glen, diverge as the book develops and she settles into her oil career. “When she's in high school and then in the workforce in her twenties, trying to find her feet, those are really taken from my own experience,” Kiesling said. “It's when she's getting into her thirties and forties, that our lives diverge a lot. But she and I definitely share DNA.”

Interested in learning more about the ever present issue of oil through a female lens? Pick up a copy of “Mobility.”

Jen Wheeler, “The Light On Farallon Island”

Jen Wheeler drew inspiration for her novel, “The Light on Farallon Island,” from Susan Casey’s non-fiction novel, “The Devil’s Teeth.” The book centers around great white shark researchers stationed in the Farallon Islands off of San Francisco. Inspired by the eeriness of the landscape through Casey’s vivid description, Wheeler created this gothic historical novel.

“The Light on Farallon Island” is Wheeler’s debut novel. “I have been working on really sprawling unfinished manuscripts since I was a teenager,” Wheeler said. “But they're all really unwieldy. I never came close to finishing anything.”

Wheeler was laid off from her dream job as a food writer in 2020, but the silver lining was severance pay which allowed her the time and space to create a complete novel. The whole process took Wheeler less than a year.

The novel follows Lucy Riley, a teacher to the lighthouse keepers’ children on the island. Shrouded with mystery, the book reels the reader in. Pick up a copy of “The Light on Farallon Island” for a moody read, and look out for Wheeler’s second novel, “A Cure For Sorrow,” coming out on Sept. 24.

Marcelle Heath, “Is That All There Is?”

Marcelle Heath’s collection of short stories, “Is That All There Is?” was inspired by Peggy Lee’s song of the same name. Heath used the haunting song as a stepping stone for the overall tone of her collection.

“It’s really a story about all these things happening that you have no control over,” Heath said of the song. “So the stories are very much drawn to mysteries and things that are beyond one’s control.”

Many of the stories in “Is That All There Is?” center around female protagonists and are loosely drawn from Heath’s own experiences navigating the world as a woman. “I would say the emotions of something happening to me in my life may inspire me,” Heath said. “Some characters are an amalgamation of people that I know or have met in my life.”

Heath’s favorite story from the collection is a list story titled, “Nine Times Gretchen King is Mistaken.” “It has remained one of my favorite stories in the collection because it’s funny and the character’s unlikeable,” Heath said. “She's an unlikable narrator, but she has a kind of a fascinating backstory, and she has a complicated relationship with her daughter.” Heath, who also, at times, had a fraught relationship with her mother, feels a personal connection to the piece.

“Is That All There Is?” is available for purchase through AWST Press, an independent literary publisher based in Austin, Texas.

Rachel King, “Bratwurst Haven”

Rachel King, author of “Bratwurst Haven,” UO Alumni and finalist for the Ken Kesey Award for Fiction, was inspired to write her collection of short stories after four years of living in Colorado, but said, “everything I’ve experienced, imagined, felt and observed goes into my fiction in one way or another.”

The stories featured in “Bratwurst Haven” explore themes of class, human connection and American culture. The stories traverse topics of how low-wage workers provide support for each other, what it means to be a Western American and the long-term impact of short-term friends.

King studied English and Russian at UO, and after completing the KIDD tutorial writing course, she was convinced to dedicate her life to creative writing.

“Writing creatively is a practice and a lifestyle,” King said. “Like that person in my neighborhood who plays the drums alone in their garage every evening while I walk my dog. I do want an audience, but to sustain the practice, I have to like doing it in and of itself.”

Explore Western American culture through “Bratwurst Haven’s” smattering of outcast characters: a laid-off railway engineer, an exiled computer whiz, a woman estranged from her infant daughter and more.